Analogy to define the problem

Imagine a child has a big box of Lego bricks of various colors. They’re asked to build a tower, but with a special rule: the bricks that are most similar to the color red should be placed at the top, and the bricks that are least similar to red should be at the bottom. Now, let’s say you introduce a condition to complete it in the shortest possible time.

In the shortest possible time, there is a chance they may make mistakes and overlook a few things due to the emphasis on speed.

Analogies are fun, but don’t try to make them too perfect – they all break down eventually!

How does this problem apply to vector search

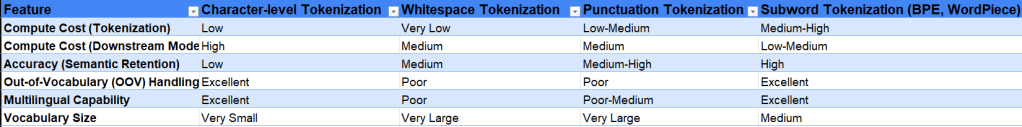

Approximation: Many use approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) techniques for speed, which means they don’t always find the absolute closest vectors, leading to slightly inaccurate rankings.

Vector Representation: The quality of the vector embeddings matters. If the vectors don’t accurately capture the semantic meaning of the data, similarity scores will be misleading.

Distance Metric: The chosen distance metric (e.g., cosine similarity, Euclidean distance) may not perfectly align with the user’s perception of relevance.

Data Distribution: Vector spaces can be high dimensional and sparse, causing the “curse of dimensionality” where distance becomes less meaningful.

What exactly happens in re-ranking

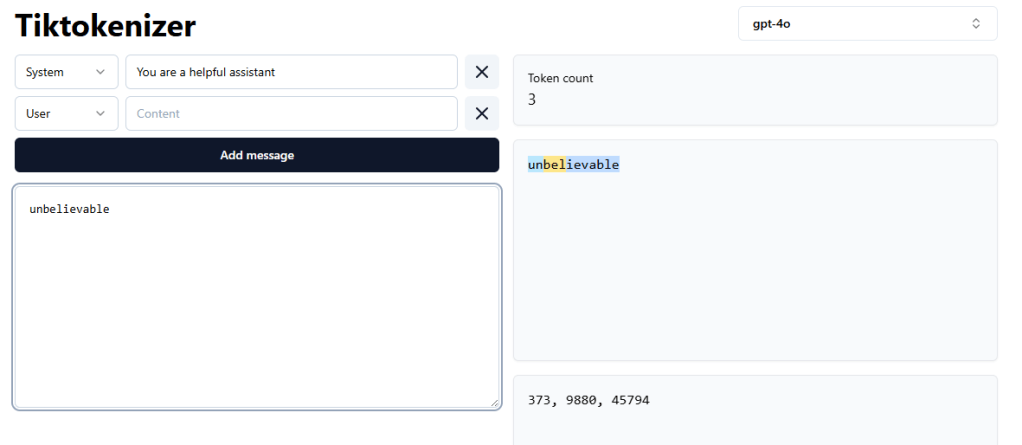

Re-ranking Model

- The initial search results, along with the query vector, are processed by an advanced model to refine relevance scoring.

- Typically, this model is transformer-based (e.g., BERT) and trained to capture semantic similarity.

- It evaluates each document in relation to the query and may also consider contextual relationships among retrieved documents.

- The model assigns a relevance score to each document, reflecting its alignment with the query.

Re-ordering

- The retrieved results are re-ranked based on the relevance scores from the re-ranking model.

- Documents with the highest scores are prioritized at the top of the results list for improved accuracy.

Example Code

import numpy as np

from sklearn.neighbors import NearestNeighbors

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

# 1. Define sample data

documents = [

"Machine learning is a subfield of artificial intelligence",

"Neural networks are used in deep learning applications",

"Natural language processing deals with text data",

"Computer vision focuses on image recognition",

"Reinforcement learning uses rewards to train agents"

]

# 2. Create vector embeddings for documents

encoder = SentenceTransformer('all-MiniLM-L6-v2')

document_embeddings = encoder.encode(documents)

# 3. Build ANN index

ann_index = NearestNeighbors(n_neighbors=3, algorithm='ball_tree')

ann_index.fit(document_embeddings)

# 4. Define user query and convert to embedding

query = "How do AI systems understand language?"

query_embedding = encoder.encode([query])[0].reshape(1, -1)

# 5. Initial Retrieval: Get approximate nearest neighbors

distances, indices = ann_index.kneighbors(query_embedding)

initial_results = [(i, documents[i], distances[0][idx]) for idx, i in enumerate(indices[0])]

print("Initial ANN Results:")

for idx, doc, dist in initial_results:

print(f"Doc {idx}: {doc} (Distance: {dist:.4f})")

# 6. Re-ranking with a more sophisticated model (simulated here)

def rerank_model(query, candidates):

# In a real system, this would be a transformer model like BERT

# Here we simulate with a simple relevance calculation

relevance_scores = []

for _, doc, _ in candidates:

# Count relevant keywords as a simple simulation

keywords = ["language", "text", "natural", "processing"]

score = sum(keyword in doc.lower() for keyword in keywords)

# Add a baseline score

score += 0.5

relevance_scores.append(score)

return relevance_scores

# 7. Apply re-ranking

relevance_scores = rerank_model(query, initial_results)

# 8. Re-order results based on new relevance scores

reranked_results = [(initial_results[i][0], initial_results[i][1], score)

for i, score in enumerate(relevance_scores)]

reranked_results.sort(key=lambda x: x[2], reverse=True)

print("\nRe-ranked Results:")

for idx, doc, score in reranked_results:

print(f"Doc {idx}: {doc} (Relevance Score: {score:.4f})")

When Re-Ranking Offers Limited Value

Poor initial results: If the first search is bad, re-ranking can’t fix it.

Uniform relevance: If everything is equally relevant/irrelevant, re-ranking is pointless.

Computational cost: Re-ranking is slow, impacting real-time use.

Relevance mismatch: The model’s “relevance” differs from the user’s.

Ambiguous queries: Re-ranking struggles with unclear requests.

Data bias: Biased training leads to biased results.

This serves as a reference to clarify my understanding of the problem, explore a potential solution, and outline its limitations.

Now, go fix some bugs! 🚀